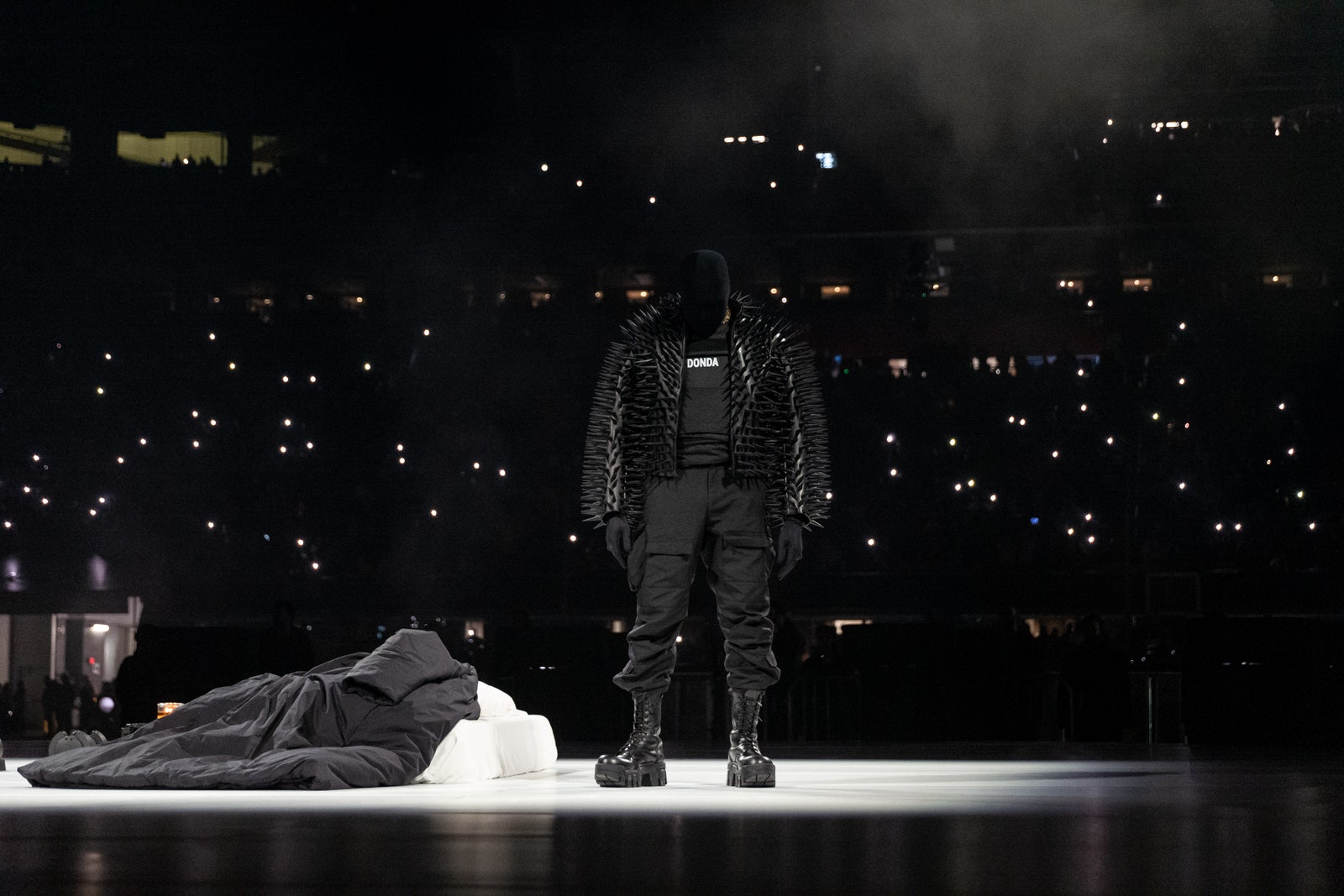

Featured Image: BFA/Yeezy via Vogue

![]()

In the full light of hindsight, seeing the past with grown conscience is a painful discovery. The only direction is tomorrow, with an offensively unfixable yesterday. “We live everything as it comes, without warning, like an actor going on cold,” Kundera paints this unbearable life. The nadirs of life’s course uncover self-knowledge, which, when woven into our textures, is a worthwhile consolation. We become woven. DONDA is Kanye’s integration of the postoperative death of his mother at 51 years old. This tragedy and his subsequent depression shape Kanye’s story — they were his absolute bottom. His rollercoaster since her death, the projected superego, high profile divorce, and political humiliation led him to Christianity, a stage upon which he searches for peace. The album follows his emotional journey from a purgatory to the enlightenment of a universalist God. DONDA, Kanye’s most life-affirming project, saves a disgraced character who “came from somewhere, not just from the wombs of our mothers and seeds of our fathers, but from a long line of generations who came before us.” His integration of his past is a surrender to God, total trust in the path his ancestors and mother have paved for him. Grief, Black political identity, and faith are brought to a trinity in DONDA, Kanye’s life’s culminating project.

I — Purgatory

Screams from the bottom of a cell — “I’m pulled over, I got priors, Guess who’s goin’ to Jail tonight?” over punching chords and a crying guitar melody. The anthemic opener colors Kanye’s psyche to start the album — the rock bottom of regret and hopelessness. This fall, when the album was released, I was in the first weeks of a move to New York with my girlfriend. Two young artists seeking an escape to the cultural Mecca, when we arrived we realized that our journeys could not continue together — we had to let each other, and our dreams together go. In a new place, and alone, my dream began to feel like daily punishment. The Manhattan-bound train opened its doors and asked, will you join the procession today? You got knocked down. It’s hard and you’re new and scared and alone, but you have to fucking try and fight. You just do. Kanye screamed the hollowness I felt in Jail. Fresh off divorce, fresh off ridicule from his politicking. Jay’s fraternal hand came down in his feature, “Pray 5 times a day, so many felonies. Told him to stop all of that red cap, we going home — not me with all of these sins casting stones” — the big brother who has seen his own rock bottom. I’d come out of the 3-floor staircase at the Grand Central Terminal, alone in a jungle, trapped underneath skyscrapers. Jail exploded in my headphones. I didn’t know where this vertiginous karma came from, or when the falling stopped. I still wonder sometimes if I’ve seen the worst of the pain, but I picked up Kanye’s response to life’s blows.

“Take what you want

Take everything

Take what you want

Take what you want” (Jail, Kanye)

The album’s opening is a cinematic dark drive through living hell. From Jail, God Breathed, Off the Grid, Hurricane, and Praise God, Kanye features a combination of doomed gregorian chants and organs and abrasive Yeezus styled grit. He integrates Atlanta slime, drill rap, Weeknd’s coked-out dreamscape, and Baby Keems’ intoxicating yells. Kanye raps about his broken marriage with a further confrontation of his mistakes.

“Here I go on a new trip, here I go acting too lit // Here I go acting too rich, here I go with a new chick

And I know what the truth is, still playing after two kids // It’s a lot to digest when your life always moving

Architectural Digest, but I needed home improvement // 60 million dollar home, never went home to it

Genius gone clueless, it’s a whole lot to risk// Alcohol Anonymous, who’s the busiest loser?” (Hurricane, Kanye)

The chorus supplicates from a place of fear “Father hold me close, don’t let me down”, knowing that his suffering was his own creation.

II — Egos, Projected Selves

Seems, madam? nay, it is, I know not ‘seems.’

’Tis not alone my inky cloak, [good] mother,

Nor customary suits of solemn black,

Nor windy suspiration of forc’d breath,

No, nor the fruitful river in the eye,

Nor the dejected havior of the visage,

Together with all forms, moods, [shapes] of grief,

That can [denote] me truly. These indeed seem,

For they are actions that a man might play,

But I have that within which passes show,

These but the trappings and the suits of woe.’ (Hamlet 1.2.76–86)

Hamlet insists on the inauthenticity of projected egos. No performance, no black clothing, or dejected looks could approximate the pain of losing his father. And yet, Hamlet obsessed himself with performances. While processing loss, Hamlet produced a play in the public theatre. He presented a manic ego, it was often unclear if he was acting or if he’d actually lost his mind. Kanye projected ego takes a similar form — “People say tweetin’ make you die early, how ‘bout have my heart hurtin’, Hold it all inside that could make you die early.” The next movement of the album, from Believe What I Say, 24, Remote Control, and Moon oscillates between his “performed-self” and his inner turmoil. From one song to the next he mocks his public divorce and flips to God-praise.

“I gave you every single thing you was askin’ for // I don’t understand how anybody could ask for more

Got a list of even more, I just laugh it off // I be goin’ through things I had to wrote

Celebrity drama that only Brad’ll know // Too many family secrets, somebody passin’ notes

Things I cried about, I found laughable” (Believe What I Say, Kanye)

The most beautiful, albeit abrupt transition on the album follows Remote Control, where Kanye insisted that his power renders the world a remote. The mocking melody ends and jumps right into a slow guitar-strummed dream. Moon is the end of the projected ego. It’s a return to the simple, an image of a youthful dream. Kanye’s child-like self emerges. The self that existed before life’s endless cycles of hurt, before guilt and shame, and before egos wrapped around us like layers of protection. Kanye and Kid Cudi, another glorious reunion, join for an ultimate acceptance of their inner child.

III — Integration

“It feels good to be home.

And to all of you, I thank you so much for your support, for your support of me for so many years, and more importantly for the work you continue to do.

What do you want me to talk about?

Well he said something that was a little bit dangerous; he told me I could talk about anything I wanted to. And you know I am my son’s mother. The man I described in the introduction — as being so decidedly different, my son. And what made the project extra special to me is, I got a chance to share not only what he has meant to me, but what he has meant to a generation.

As one writer said, we came from somewhere, not just from the wombs of our mothers and the seeds of our fathers, but from a long line of generations who came before us.” (Donda, Donda West)

Donda, the album’s climax, an enlightening moment of glory, the realization that mistakes and suffering are not steps away from the Path. Donda is a return home, and a respite to the mental anguish and wounds of heartbreak. The chorus erupts from the end of Donda’s spoken word, a prayer from the Gospel of Matthew, and the album’s most life-affirming moment. For the first time, and for the remainder of the album, the choir sings glory instead of hopeless search. Kanye’s purgatory, manic projected ego, and hopelessness lead to this moment of realization that his God is a universalist one. All punishment is temporary remediation and God will not wholly destroy a single soul. This doctrine guides the rest of the album. His guilt and ego are revisited, but with an integration of universalist belief, that he too will be saved.

Jesus Lord is Kanye’s advocacy for practicing radical mercy. His argument for the release of Larry Hoover, Sr. from his maximum security prison is an argument for abolition. That God’s mercy supersedes his wrath, and we deserve forgiveness and to be saved in this world. For the first time since he wore the red cap, Kanye’s politicking is in service of God over his own ego. The album closes by revisiting themes of divorce and grief.

“Startin’ to feel like you ain’t been happy for me lately, darlin’

‘Member when you used to come around and serenade me, whoa

But I guess it’s gone different in a different direction lately.” (Lord I Need You, Kanye)

Now, on the other side of his surrender to his path, the chorus reminds that “God got me and God got the children.” His grief continues to live with him. He admits that he sometimes wishes for a different life. “I don’t wanna die alone, I don’t wanna die alone,” but floating on a silver lining, with choral Hallelujah’s woven throughout the instrumental, he’s free from the Jail that opened the album.

DONDA is a story about integrating life’s unnavigable waters. Kanye isn’t a sympathetic public figure. After Yeezus, he became indefensible. This record was necessary about face. His devotion and abolitionist politics rose from the ashes of his grief following the loss of his mother and divorce.

In this new life, it is enticing to start all the way over. DONDA urges for integration and the pursuit of a woven self.

Leave a Reply